During Tuesday's UN Climate Summit in New York City, leaders from 125 nations, along with representatives from businesses, civil society and other institutions, convened and pledged to continue their efforts in fighting global climate change. Like many countries, China stopped short of making any post-2020 commitments at the Summit, though Vice Premier Zhang Gaoli announced that China will work to peak its total CO2 emissions as soon as possible. He also described China's successes to date on energy conservation and renewable energy, reaffirmed China's commitment to meeting its 2020 carbon intensity reduction target, and pledged 6 million U.S. dollars in support of the South-South cooperation fund on climate change. My colleague has compiled a list of China's actions and commitments here.

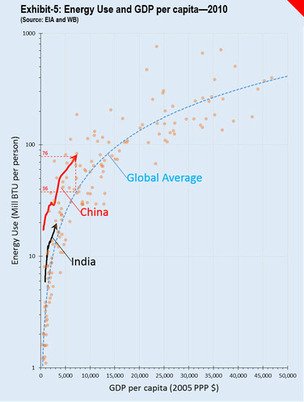

At a press conference following these announcements, Minister Xie Zhenhua, Vice Chairman of China's National Development and Reform Commission, said that China would try to submit its "intended nationally determined contributions" to a post-2020 global climate agreement in the first quarter of 2015, three months earlier than its previous pledge. This is welcome news, especially in the context of several new reports demonstrating how essential China's contributions will be to global efforts to tackle the grave challenge of climate change. According to the Global Carbon Project's annual update, China's CO2 emissions, driven mostly by its heavy reliance on coal, accounted for more than 60% of the increase in global emissions over the last decade, and now total almost 30% of all global CO2 emissions. Another study by CO2 Scorecard concluded that China is developing on a more carbon-intensive path than average, due in large part to three decades of support for energy-intensive industrial development.

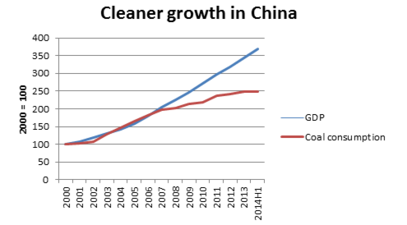

Yet in addition to climate change, China has other strong reasons of its own to transition away from a coal-fueled economy dominated by highly-polluting heavy industry – namely devastating air pollution and the need to restructure its economy to ensure continued economic growth. As my colleague Alvin Lin has explained, China is moving ahead with a number of ambitious policies designed to cut coal use, scale up efficiency and renewable energy, and promote low carbon development. These efforts are already bearing fruit. After two decades of leading the rise in global coal consumption, a new report by Greenpeace indicates that China's demand for coal actually declined in the first half of this year, even as its GDP continues to grow. In other words, assuming that the underlying GDP, energy and coal consumption statistics can be validated, China has begun to decouple economic growth and coal consumption, leading some analysts to believe that coal use in China may peak as soon as this year.

A peak in coal consumption does not automatically lead to a peak in CO2 emissions; other emission sources, such as oil use in China's growing transportation sector, must also be addressed. Yet these promising developments, along with China's plans to set further limits on coal, including mid- and long-term coal consumption cap targets, should serve to strengthen China's level of ambition regarding its post-2020 CO2 emission reduction contributions. As the IMF calculated in a recent working paper, reducing CO2 emissions not only benefits the planet, but is also very much in China's own national interest.