Editor's note: On December 2021, China's Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs released the 14th Five-Year Plan for Fisheries Development, which clearly states that China will strengthen fisheries reform and innovation, implement reforms in the management of fishing ports, and establish a comprehensive monitoring system for fisheries based on fishing ports. NRDC recently issued a report entitled "Dockside Monitoring and Seafood Traceability in the EU". Here we briefly introduce the key elements of the EU system and make suggestions for the promotion of related work in China in the 14th Five-Year Plan.

Background

The implementation of the output control system in fisheries management, such as the Total Allowable Catch (TAC), is one of the most important reforms that China is undertaking to help rebuild domestic fishery resources and promote the sustainable development of marine fisheries.

China’s central, provincial and local fisheries authorities have been actively exploring the pathway since the 13th FYP period, and have identified the essential role of fishing ports. As the junction point between the waters and land areas, fishing ports can play a key role in preventing the landing of IUU catch, collecting catch data, establishing a seafood traceability system, and directly supporting output management.

How to build a monitoring, control and inspection (MCS) system with fishing ports as the core that considers the characteristics of China's fisheries and draws on international experience?

The EU provides a good case study. EU is the world’s largest seafood importer and, in recent years, has given high priority to combatting IUU (Illegal, Unreported and Unregulated) fishing. It is one of the few regions globally that requires full supply chain traceability of all catch and farmed products in its waters, whether for food or feed purposes. Secondly, the high diversity of fishery types, the large number of small-scale fishing vessels, the presence of multi-species fisheries, and substantial institutional and structural variability both among and within the Member States (MS) require implementation strategies that balance standardization and flexibility and rely on effective coordination between MS and the EU.

Considering the similarities between the EU and China in terms of the importance attached to fishing ports, the characteristics of fisheries, and the challenges faced, the EU experience provides some helpful lessons.

Small scale vessels (< 12 m) accounts for 73% of Spain national fleet (not including distant-water vessels) @Li Wei

Small scale vessels (< 12 m) accounts for 73% of Spain national fleet (not including distant-water vessels) @Li Wei

Features of the EU's Dockside Monitoring and Seafood Traceability

To the EU, Fishing ports are the first line of defense to prevent IUU catches from being landed and safeguard the legality of seafood, the key point for collecting landing data and the starting point for traceability systems.

In general, through detailed regulation, the EU identifies a number of stages that the catch must move through before, on and post-landing, and standardizes control operations and documentation of each stage, taking into account the different circumstances of large and small fishing vessels. European Fisheries Control Agency (EFCA) assesses the MS implementation through field inspections, remote monitoring and experts’ evaluation, and strives to mitigate the substantial differences among MS through capacity building and financial incentives. In short, these controls and inspections are greatly supported by information technologies.

There are several key features:

1. Coordinated port control measures

(1) Prior notification by electronic logbook before landing. Prior notification of a vessel's entry into port gives the competent authorities sufficient time to assess whether to inspect it and to prepare the necessary resources and manpower. All EU fishing vessels engaged in commercial fishing over 12 metres in length must provide a four-hour advance notification.

For large catches (e.g. some pelagic fish) or specific species (e.g. bluefin tuna), some ports may not have adequate inspection capacity. In such cases, certain ports, opening hours, and specific locations for landing those species may be designated. Transshipment at sea is prohibited in the EU and can only take place in designated ports. Designated ports are not only larger, better equipped and have more specialized inspectors, but also consider additional factors such as proximity to fishing grounds or consumer markets.

(2) Weighing at the point of landing for completing the landing declaration. Collecting catch data after leaving the port would be difficult, so the EU requires that catches must be weighed in the port area on certified scales. These data are then used for completing landing declarations, sales notes, and transport documents. The data in landing declarations is essential information for MS to fulfil the EU Data Collection mandate and make key management decisions, including TACs. Collection of data on landings from fishing vessels smaller than 10m can be done by sampling or based on sales notes.

Adjustments requested by a MS such as allowing large vessels using a sampling approach or allowing weighing on board require EU approval and close oversight. Ireland used to allow the weighing of catches after transport, but an EU audit found problems including scale falsification which led to the approval being withdrawn.

Chinese fishermen also regularly weigh their catches at port, but there are no legal requirements for data collection in fishing ports yet. @Li Wei

Chinese fishermen also regularly weigh their catches at port, but there are no legal requirements for data collection in fishing ports yet. @Li Wei

(3) First sales can only be made through auction centers or registered buyers. The advantage of auction houses is that they provide a centralized space for verifying catches entering the supply chain and controlling the critical traceability stage of the first sale.

Vessels landing into markets for auction must provide logbook catch data to match all landings. The auctioneers are responsible for weighing (and are accountable for the accuracy of the data), attaching traceability labels, and collating and sending first sale information to the authorities. Thus, although auctioneers are not law enforcement officers, they can still play a data verification role. The third-party organisation responsible for running this may be a state enterprise, as used in Portugal, or a local association or a cooperative as is common in Italy or even a service by the port authorities.

Auction houses also provide a more centralized place for enforcement officers to carry out inspections, with national and regional fisheries authorities, port police, civil guards, and EU inspectors carrying out regular or irregular spot checks.

A port police officer is patrolling the auction hall of Port Vigo @ Li Wei

A port police officer is patrolling the auction hall of Port Vigo @ Li Wei

(4) Lot number and key data elements for achieving traceability

Full supply chain traceability of the seafood products in the EU serves multiple purposes. In addition to safeguarding food safety and preventing seafood fraud, traceability is a second line of defense to prevent IUU catches from entering the supply chain and safeguard the legality of seafood. The catches of small-scale vessels are also included in the traceability system. Traceability regulations also apply to fish below the minimum conservation reference size brought ashore following the "discard ban". "Discard ban", also called "landing obligation", refers to that all catches of species regulated through catch limits or minimum size should be landed and counted against the fishers' quotas.

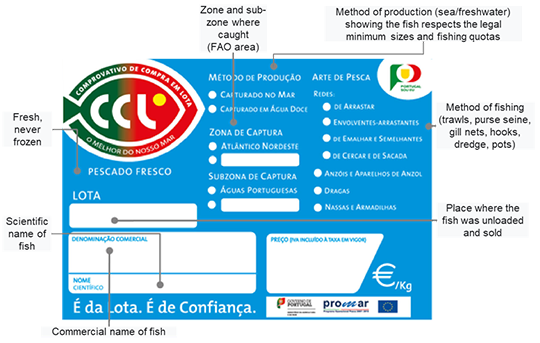

When landed, the catch will be divided into units or batches called "Lots" - these will be traceable units. A unique number is assigned, usually at weighing, to a "lot" of fish. Along with the Lot number, the key data elements required by the EU will be recorded in the traceability system (such as Lot number; the commercial name and scientific name; production method; catch area (ICES)/ Country of origin; category of fishing gear used; net weight and so on). Various documents accompanying the catch such as sales note, transport documents, commercial invoices, etc., as well as QR codes and barcodes will contain this Lot number, helping to trace seafood at any stage back to the landing event of a specific fishing vessel.

The seafood label is an effective traceability tool. The label for fish at the first sale will show the complete "lot" information and will be passed on to the first buyer. The EU also sets out the minimum information to be displayed on labels to consumers. Between the two stages, the catch may undergo various changes such as processing, splitting, or merging. MS may allow operators more flexibility to adopt traceability, as long as they can trace back to the lot number. Currently, barcodes and QR codes are widely used.

Catch label attached to fish on first sale at the auction house in the Port of Vigo, Spain, showing key traceability information @Li Wei

Catch label attached to fish on first sale at the auction house in the Port of Vigo, Spain, showing key traceability information @Li Wei

A consumer-facing seafood label promoted in Portugal @Docapesca

A consumer-facing seafood label promoted in Portugal @Docapesca

2. A risk-based and level-playing field approach to port inspection

Fisheries inspectors cannot inspect every landing vessel. A MS generally sets baseline inspection rates in their annual plans (by port/month) (e.g. Ireland has an inspection rate of approximately 5% for its own fishing vessels). They screen vessels with high IUU risk through various risk assessment methods to improve the efficiency and accuracy of fishing port inspections, but random inspections are also possible.

The EU has established an inspection list for fishing vessels prior to arrival, landing and first sale that includes vessel identification, fishing logbooks, compliance with fishing gear and other management requirements, to which MS may have the right to add inspection items.

Inspecting VMS recordings at port @ Sea-Fisheries Protection Authority, Ireland

Inspecting VMS recordings at port @ Sea-Fisheries Protection Authority, Ireland

To ensure equivalent levels of monitoring and surveillance across the EU, the EFCA looks for similar inspection rates of vessels and coherence in the rules and procedures for dockside monitoring. EFCA monitors inspection rates and infringement sanction results, and also monitors the number of vessels landed in individual ports; for example, a sudden high volume may be a sign of weakness.

Electronic enforcement databases are now in place in all MS and the format of inspection data is standardized, facilitating remote monitoring and comparison in the EU. But, the competence of inspectors in MS can vary substantially. The EU's approach to improvement is mainly providing training, enhancing exchange and cooperation among inspectors, and highlighting the sharing of best practices.

Post-landing inspections, including at first sale, transport, processing and distribution, and retail, are usually separate from the fisheries authorities' inspection plan. Depending on the MS, fisheries, food, environment, customs and other authorities at all levels may be involved in enforcement.

3. Modern technology that transform traditional fisheries control

EU's significant progress in implementing the control regulation can be attributed to promoting information technologies, particularly VMS and electronic reporting systems. The advantages of electronic logbooks can be found in another NRDC report E-reporting in Fisheries.

In addition, as MS share EU waters and it is common for flag states and port states to differ, exchange of logbooks, catch certificates and inspection data electronically between MS, together with the standardization of data formats, allows the relevant authorities to quickly obtain the necessary information for control purposes.

Digital tools also greatly enhance the effectiveness and efficiency of traceability, reduce human interference with the quality of information and eliminate the possibility of repeated use of the same catch document. It can be said that without efficient technical support, it would be difficult for the EU to achieve effective traceability of all catches.

Lessons from the EU experience

After the MARA issued the Circular on Further Strengthening the Control of Domestic Fishing Vessels and Implementing the Total Management of Marine Fishery Resources in 2017, China has been actively deploying designated landing ports for medium and large-sized vessels, established a Hail in and Hail out system nationwide, and carried out a national pilot project on comprehensive management reform of fishing ports in Taizhou, Zhejiang Province, exploring the catch legality label, as well as developing relevant laws and regulations.

In light of the above three main features of the EU's "port-based fisheries management" system and related experience, we suggest that in the 14th Five-Year Plan period:

(1) In terms of control measures, local fisheries authorities should continue to conduct pilot projects in designated fishing ports to explore how to coordinate and combine control measures such as hail in and hail out, VMS and electronic logbooks to support catch data collection and the TAC system. In addition, they should actively communicate with national fisheries authorities to explore possible unified standards.

In particular, to achieve a more comprehensive collection and verification of catch data and to complement the random inspection system of fisheries enforcement officers, the role of research institutions, universities, technical extension agencies, as well as fisheries organisations at all levels, needs to be fully explored and brought into play.

(2) In terms of enforcement and compliance, there is a need to vigorously strengthen the support for the construction of the fishery administration team, actively carry out capacity building, enhance the theoretical knowledge and practical skills of enforcement officers in fishing port enforcement, and achieve a relatively consistent level of port control.

(3) In terms of improving efficiency and strengthening coordination, China should introduce a series of information technology tools in fisheries monitoring, supervision and enforcement, data management, etc., such as electronic logbooks/certificates, satellite tracking technology, smart weighing equipment, and QR codes/barcodes.